In Praise of Subject Matter Experts

There’s a meme doing the rounds on the internet at the moment that describes the author’s dilemma as this: we write characters into tight corners so that they can demonstrate their ingenuity in getting out of those tight spots… but then we, the authors, are faced with the problem of figuring out what those ingenious solutions might be.

In the succinct words of the meme’s author, Paul Kreuger: “I forgot one key detail: That escape is to be written by me, a dumbass.”

This meme kept coming to mind in the writing of The Paris Deception because both Sophie and Fabienne, my two protagonists, have exceptionally specialized skill sets, one as an art conservator and one as an artist: and much as I’d love to have Fabienne’s talent with a paintbrush, the only sort of painting I’m good at involves drywall and plaster. But that’s where we authors have the benefit of our social and professional networks – and if we ask around, and are incredibly lucky, we can find subject matter experts who can help us bring our characters to life and find those ingenious solutions to the problems we create.

In the case of The Paris Deception, my old university roommate, Nastasia, was able to plug me into the world of New York City’s art conservation community through a friend of hers from high school. In the span of a single email, doors opened: I flew to New York City and was given private tours of the art conservation labs at the Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art. I learned about the history of art conservation and how attitudes towards conservation have changed from the 1940s, when the watchword for conservators (then known as restorers) was to make pretty, rather than acknowledge the entire history of an artwork; I learned about the sorts of tools that a conservator in the 1940s would have at her disposal, and how conservators rely on different materials and conservation paints so that their work can be recognized and removed by future conservators. I was introduced to the meticulous and respectful process of conserving religious objects and artefacts at the Museum of Natural History, and was shown a Van Gogh partway through a conservation treatment at MoMA, right up close, behind the velvet curtain.

Being an author involves being a jack of all trades and a master of none: we don’t always have the luxury of stepping into our characters shoes professionally, but having access to subject matter experts gives us unique insights into how our characters might think, feel, and approach their lives. They also keep us from making the sorts of mistakes that are incredibly obvious upon reflection: for example, situating a fictional art conservation lab in the basement of a museum. At first glance, it makes sense – museums would want to use as much of their premium space for galleries – but conservators need natural light in order to match their paints properly, so most conservation labs tend to be located in attics or on top floors.

The same sort of obvious mistake was caught by a friend in the winemaking world who explained to me, with the patience of a parent telling a toddler that their stuffed animal can’t eat tomato soup, that a champagne cave would be exactly the wrong place to store a painting because the humidity would ruin the canvas.

A subject matter expert was especially helpful in solving Sophie’s problem of getting the artwork out of the museum undetected. While one method of smuggling art (hiding the canvas within the lining of a raincoat) was something I’d learned from a university professor who’d used the method to smuggle banned literature into Soviet Russia, the second method of smuggling came courtesy of another conservator.

“Well,” he said, wrinkling his brow when I asked how a conservator such as himself might get a priceless work of art out of a museum, “I’d line the painting with a second canvas, paint a different picture over it, and then remove the second canvas later.”

We authors are fortunate in that we get to learn about different industries and professions that don’t necessarily align with our own experiences. We get to live through our characters and live, momentarily, within their worlds: take on their daily grind, and break free of it in unexpected ways. As the saying goes, good artists borrow, great artists steal… and writers, when we’re lucky, can consult the experts when we need to get our characters out of painted corners.

Bryn Turnbull

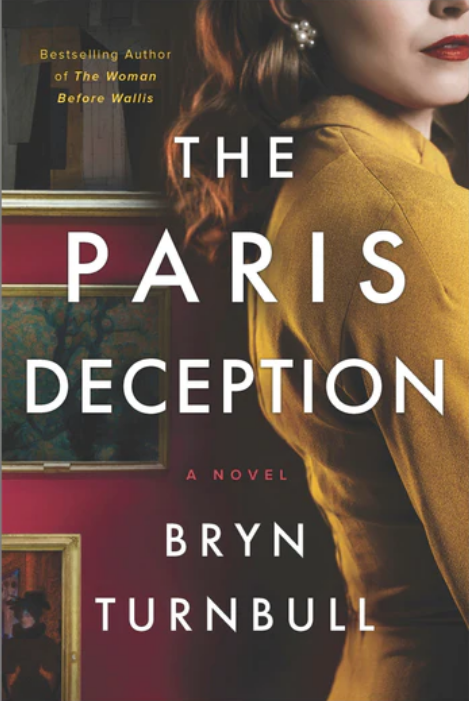

The Paris Deception by Bryn Turnbull

From internationally bestselling author Bryn Turnbull comes a breathtaking novel about art theft and forgery in Nazi-occupied Paris, and two brave women who risk their lives rescuing looted masterpieces from Nazi destruction.

Sophie Dix fled Stuttgart with her brother as the Nazi regime gained power in Germany. Now, with her brother gone and her adopted home city of Paris conquered by the Reich, Sophie reluctantly accepts a position restoring damaged art at the Jeu de Paume museum under the supervision of the ERR—a German art commission using the museum as a repository for art they’ve looted from Jewish families.

Fabienne Brandt was a rising star in the Parisian bohemian arts movement until the Nazis put a stop to so-called “degenerate” modern art. Still mourning the loss of her firebrand husband, she’s resolved to muddle her way through the occupation in whatever way she can—until her estranged sister-in-law, Sophie, arrives at her door with a stolen painting in hand.

Soon the two women embark upon a plan to save Paris’s “degenerates,” working beneath the noses of Germany’s top art connoisseurs to replace the paintings in the Jeu de Paume with skillful forgeries—but how long can Sophie and Fabienne sustain their masterful illusion?

Available at:

Amazon | Barnes & Noble | Google Play | Kobo | Apple Books | Indiebound | Indigo | Audible | Goodreads